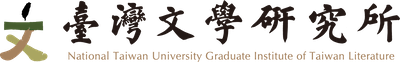

The Eng-Lite Program Lecture Series: Talk No 2

Time:2023.09.27(Wed.)14:30-16:30

Topic:Translation, Disinformation and Wuhan Diary

Speaker:Michael Berry, Professor, Department of Asian Languages and Cultures, University of California, Los Angeles

Host:Hsin-Chin Evelyn Hsieh, Associate Professor, Graduate Institute of Taiwan Literature, National Taiwan University

Venue: NTUGITL R324, Guo Qing Bldg.

By Conrad C. Carl

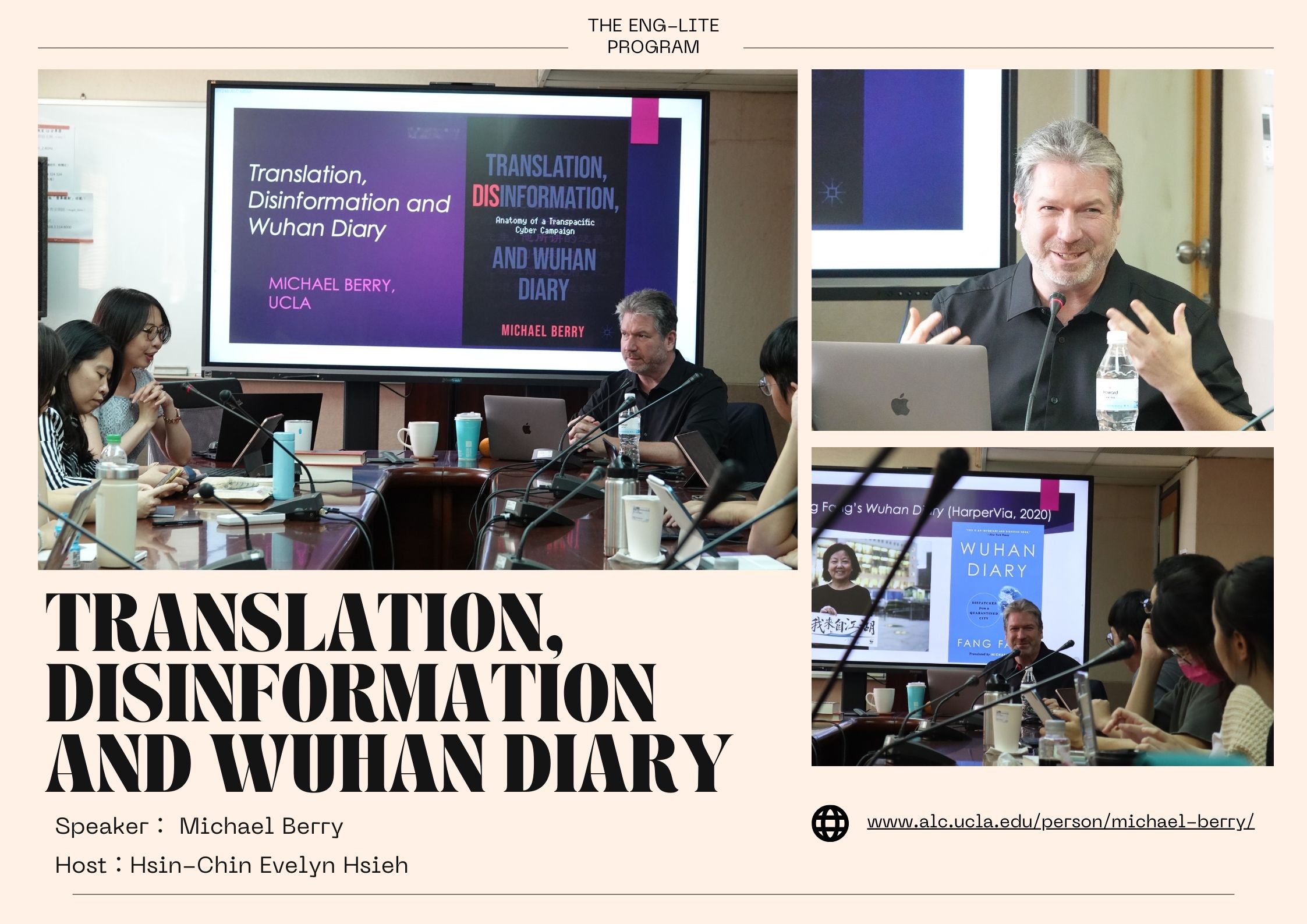

On September 27, 2023, we were honored to have with us Michael Berry—Professor of Contemporary Chinese Cultural Studies at the University of California (UCLA). The COVID-19 pandemic was without a doubt the most drastic event of recent times. And while questions about the post-pandemic condition are pressing, it is still necessary to reflect on the events that led to where we are right now. What made Professor Berry’s presentation particularly powerful is the fact that it combined questions of integrity, responsibility, political and public hegemony with explorations of the power of literature and personal accounts.

The first and main protagonist of Professor Berry’s talk was Fang Fang. Fang Fang—an acclaimed Chinese author—chronicled the first city-wide lockdown of the COVID-19 era lasting 73 days in the Chinese city of Wuhan in an online blog called “Wuhan Diary.” Her writing style was raw and unpolished with occasional mistakes which is testament to the immediacy and authenticity of the posts. As a source of information regarding anything COVID-19-related, it went viral and reached hundreds of millions of people. Her accounts included quotidian details about people’s lives during the lockdown, updates about local hospitals, stories of friends, family and neighbors, as well as news report summaries. With time passing by, she also addressed internet censorship, disinformation, accountability and similar issues, earning her criticism by the CCP, for they feared the destabilizing effect her blogging would potentially cause. Eventually, this led to one of the most nefarious defamation campaigns in recent history on Chinese soil, and Michael Berry found himself right in the midst of it.

But how did an online blog spark a nationwide debate? As always, the context was important. As Professor Berry emphasized, the attacks on Fang Fang are only understood in the broader dynamic of how the CCP dealt with other whistleblowers. Li Wenliang—the doctor initially raising concerns about COVID-19—was subjected to heavy censorship and suppression and was only posthumously turned into a heroic figure. Or Zhang Zhan—an investigative and independent journalist—who was arrested for her reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic and sentenced to four years in prison. In both cases, controlling the narrative was the guiding principle of the CCP. That being said, instead of creating yet another martyr in Fang Fang, someone who generally enjoyed a good reputation and political standing, the CCP chose a different approach: disinformation and defamation. Instead of locking her up, they attacked her credibility and authenticity, claiming that whatever she posted was merely hearsay. They also propagated conspiracy theories, alleging that she was affiliated with the US government and thus tried to influence the narrative about the origin of the virus. But—as Professor Berry stressed—the campaign went further: Internet trolls, government backed groups and individuals, such as Anti-Fang Fang intellectual “hitmen,” orchestrated personal attacks on Fang Fang and anybody associated to her. Any supporters were silenced. The CCP made use of everything at their disposal. This included not only negative disinformation campaigns, i.e. purporting what Fang Fang reported on was wrong and publications should be prevented, but also the promotion of ostensibly credible alternative narratives.

Professor Berry was the first to translate Fang Fang’s blog into a full volume book. While Fang Fang was still blogging, Professor Berry had already started the English translation. With only vague awareness of the situation in China, the American public—or rather English-speaking people everywhere—deserved to know more about what was going on. In other words, it was a sense of historical mission that drove Professor Berry’s translating pace to a staggering 5000 words per day. But this also meant that there was a target on his back now. Once his translation was published, internet trolls flooded websites with negative reviews and used several platforms to discredit and threaten him, incorporating him into their conspiracy theories.

As Professor Berry emphasized, there was a lot at stake for the CCP. This included rather abstract but unpredictable ramifications, such as the potential loss of control over the narrative, combined with more immediate threats to the CCP’s standing. Fang Fang’s accounts had the potential to lead to concrete questions of international reparations, particularly regarding the origin of the virus and the ensuing cover-up. Distracting the Chinese citizens by directing their anger towards external targets, such as the US and Professor Berry, was thus the main strategic goal of the CCP. They aimed to regain control over larger debates about civil society, too. Uniting a fractured society or finding common ground in the debate between nationalism and liberalism were crucial in shifting the emphasis from centrifugal trauma (internalized crises leading to destabilization) to centripetal trauma (external attacks leading to a nationalistic response). The treatment of Fang Fang was more sophisticated and orchestrated, with social media and troll culture playing important roles in its success.

What lessons can be learned from Fang Fang? While it all started with an online blog, Fang Fang’s Wuhan diary and the responses it created raised issues about compliance with healthcare protocols, accountability (specifically in authoritarian societies), as well as questions about the dynamics of civil society, disinformation, courage in the face of threats and defamation and—related to this very point—the importance for everyone to tell their own story and the power of literature to both bear witness and shape the world.

With the presentation over, the audience raised several questions, for instance related to disinformation and the means at our disposal to deal with them. Although we arguably live in the post-truth era, we should refrain from conflating different kinds of disinformation regimes, Professor Berry asserted. The people in the PRC are exposed to one version of reality, while in Taiwan, there are many. There is disinformation here, too. But different narratives and accounts of truth are contested and debated, something which this talk was testament to. Unrelenting figures like Fang Fang, who stand their ground despite intimidation, threats and defamation, Professor Berry underlines, deserve our recognition, admiration and support.

And Professor Berry undoubtedly belongs to this category of unrelenting figures, too. We thank Professor Michael Berry for his talk and invite anyone interested in this story to read his book Translation, Disinformation and Wuhan Diary: Anatomy of a Transpacific Cyber Campaign (2022).